The Importance of Gullet Width

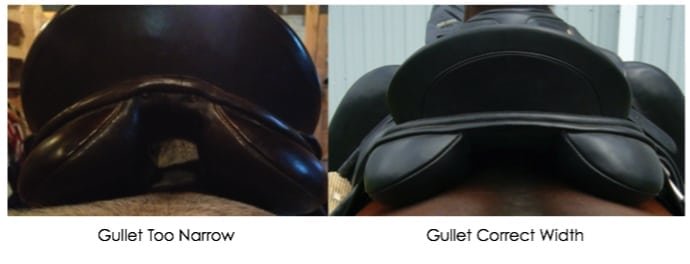

In the course of fitting and selling saddles a very common question that I get is about the width of the gullet or the space between the panels for the horse’s spine. The general consensus tends to be that if it isn’t touching the bones of the spine then it must be wide enough. This is completely untrue. I worked with a horse not long ago, an 8 year old Anglo-Arab gelding, that had a mystery front end lameness. He was never horse-headlame on the same leg day to day and would also have some moderately sound days. The owner was getting ready to retire him because the veterinarian could not find anything physically wrong. Saddle fit was her last thing to check before throwing in the towel. I examined this horse and noted that he was extremely tight all along his spine. When I turned his current saddle over there was 1.5” of clearance between the panels. When I measured his spine it was 3” wide. When he was fitted with a 4” wide gullet he was completely sound. He went from daily lameness to no lameness in a matter of minutes. In this post I would like to explore why this would happen!

Interestingly, when we examine military saddles made over a century ago we find quite a wide space between the panels, which we call the channel or gullet. However, in looking at the most popular English saddles designed just two and three decades ago we discover that some apparent anatomical knowledge must have been lost in translation as the English style of riding saddle came into existence. Gullet spaces had become surprisingly narrow! One core principle which has been constantly affirmed throughout my more than fifteen years of saddle fitting is the great importance of channel width on a saddle. In more recent years the trend in Dressage saddles is returning to this wider gullet style. As we look analytically at the structure of a horse’s back it becomes evident why we need to keep the saddle from interfering with the spine and surrounding anatomy.

At their origin, English style saddles were designed to clear only the spinous process. This is the top ridge of vertebrae that you can feel on the typical equine by pressing your fingers deeply along the very center of the back. It makes sense that spinousno creature would enjoy a weighted and strapped piece of athletic equipment rubbing, bumping or pinching tissue against these bony processes. In decades past, the average English style saddle was widest at the wither area, narrowing often severely through to the rear. Looking at a horse’s skeleton, we see this mirrored. The spinous processes are wider at the start of the withers and become narrower toward the loin. That does make some basic sense.

However, in choosing and fitting a saddle we need to be aware that there are also junctions of muscle groups vital to free movement all around the wither area. Two important muscle groups overlap here: The multifidus and semispinalis. The multifidus is a set of highly innervated, deep muscles which lay closely along the spine, stabilizing and supporting the inter-vertebral joints. The semispinalis muscle group joins the base of the neck to the wither and back. A saddle needs to clear this area entirely to allow comfortable extension and elevation of the neck and shoulder.

Initially neglected in less recent English style saddles were also the muscles and ligaments running along the thoracic spine – the portion of the back where ribs attach to vertebrae. These areas also require special attention during fitting. Like any other manufacturer of athletic equipment, as we gain more detailed knowledge of the dynamic movement of the horse under saddle we make improvements, though sometimes with the added challenge of an equestrian culture steeped in tradition. The most ridiculous arguments ever made in the saddle fit world are any against progress. True saddle fitters put horses first. We constantly desire and eagerly strive to improve equipment to better accommodate our equine partners.

With all of this considered, we still may wonder the finer points of why gullet widths have increased and why it is so important that they have. Running along the top of the horse’s spinous process is the supraspinous ligament. This same stretch of ligament actually originates at the poll, where it is known as the nuchal ligament. This crucial ligament attaches to 7 cervical vertebrae in the neck and continues over the wither. Equine Thoracic Vertabae, gullet width, saddle gulletLike a street might curve and change in name to confuse you and your GPS, this same ligament is called the supraspinous ligament from the base of the withers all the way to the point of the croup. This bridge along the top of your horse’s spine represents two-thirds of the ligaments responsible for the stretching of head and neck, along with how the back of the horse is raised and rounded upward or dropped and hollowed. This supraspinous ligament runs directly under the saddle and rider. Naturally, we do not want to interrupt the actions it needs to perform. When the back is raised this ligament system allows the longissimus dorsi (back muscles) to work in a relaxed and free manner while remaining engaged. Understanding how your horse moves makes it easy to understand that the gullet channel of the saddle must be wide enough to clear this ligament completely.

The next area critical to movement and important to consider for channel width are the multifidus muscles. This segmented muscle group mentioned earlier lies right next to the bones of the spine. Some parts of this muscle start as far back as the sacrum. They run forward and upward in segments, interlacing and attaching on either the tops or the sides of the dorsal spinous processes, each terminating a few vertebrae ahead of where they start. This is another dynamic system which helps to support and extend the spine. Also, when these muscles are active laterally they can contract one side of the spine or the other, contributing massively to bend and flexion in the back. This is where gullet channel width becomes especially vital.

If the saddle is too narrow between the panels it can hamper lateral movement of the multifidus muscles, making the horse very stiff and resistant to bend. This will also cause the horse to have a tendency to hollow and contract the back. Leaving these muscles unrestricted is essential to having a loose, relaxed and swinging gait.

Lastly we need to look at the intervertebral foramina – the spaces through each vertebra which allow nerves, blood vessels and lymphatics to exit the bony canal at each segment. These spaces lie between the arches of each vertebral body and are formed by ventral notches in the front and back of the vertebral arch. A gullet which is too narrow forces pressure on the areas where these vital soft tissue systems exit the spine and can cause a host of issues for the horse, including the ever-elusive mystery lameness. It is extremely important to clear not only the upper ridges of the vertebrae but also the transverse processes at the sides.

I also want to make the point that your gullet can be too wide as well. There are no horses in existence that need 6” of space between their panels. Usually a horse will need from 2”-4” from panel edge to panel edge to achieve good clearance. If we go overboard and create saddles that are too wide one of two things will happen: Either the saddle will sit down on top of the horse’s spine which negates the whole purpose of a gullet in the first place or we have to build the saddle up so high to get clearance on the bones of the spine that the rider is sitting extremely far from the horse. Neither of these outcomes are ideal so it is extremely important that this is measured correctly. Many saddles on the market now this width could and should be adjusted from horse to horse.

It is clear why space without contact is needed throughout gullet and along the spinal column, but one more factor must be considered: The inevitable motion of the saddle on the horse’s back. The amazing equine body moves in many different ways dependent upon gait, direction and changes in elevation just to name a few factors thrown into the mix. The best place to see this thought in action is at the canter, most dramatically at the canter on a circle.

When the horse is cantering – on the right lead for example – the foreleg on the opposite side (left in our example) is slightly dropped. This has absolutely nothing to do with the quality of the rider, the horse or the equipment. Following this motion, a properly fitted saddle will always sit slightly to the left. The same principle can be seen as the saddle sits slightly to the right in the rear during left lead canter with left bend. Canter is the most valuable gait I use as a saddle fitter to examine saddle straightness.

If the gullet of the saddle is not wide enough then during any kind of bend, especially in the canter, the panel will push against the side of the spine inhibiting the mutifidus muscles and in worse cases even interfering with the supraspinous ligament, which are both crucially important for collection and self carriage of the rib cage. We need this suspension system to be free for it to work properly so that our horses are able to move correctly and soundly without restriction. The more educated we are in the biomechanics of the horse, the more we realize the importance of all of these systems. Understandably, keeping these systems healthy and functioning properly goes a long way in preventing back problems such as kissing spines – an issue for another article altogether.

From thermography, to the recording and mapping of subtle changes in gaits frame by frame using trackable points, all the way to cameras injected directly into muscle, the study of how a horse moves has grown leaps and bounds in recent years. All of this information and technology allows us saddlers to constantly change the paradigm of what correct saddle fit is so that we can give you the best information right now as to how to fit a saddle properly. It is guaranteed that saddle fit will continue to evolve as technology grows. Saddle manufacturers and fitters will follow suit in this evolution. The ultimate goal of a true saddle fitter is to keep both equine and human athletes comfortable, healthy, sound and free to stride toward fulfilling all their performance potential.